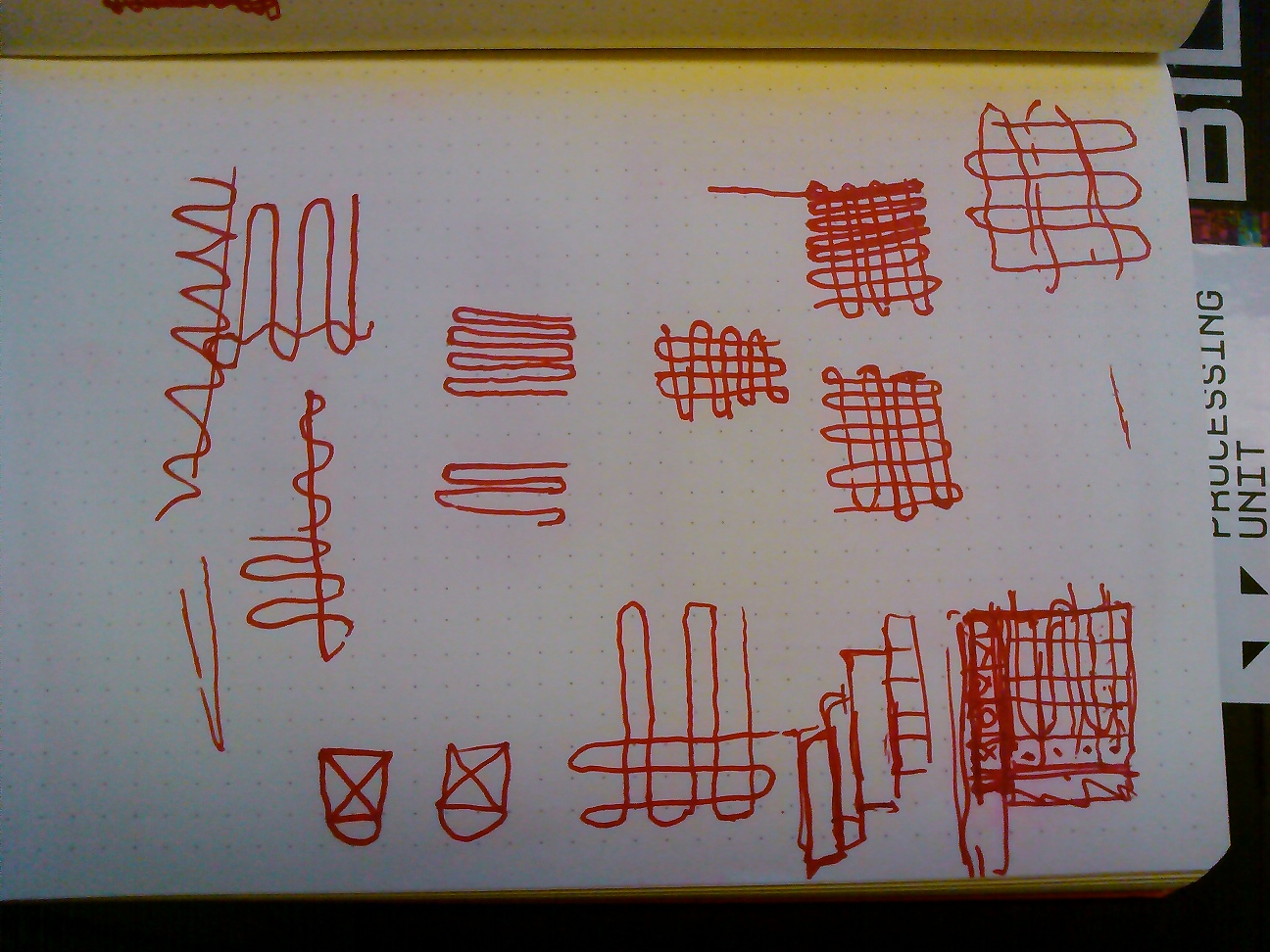

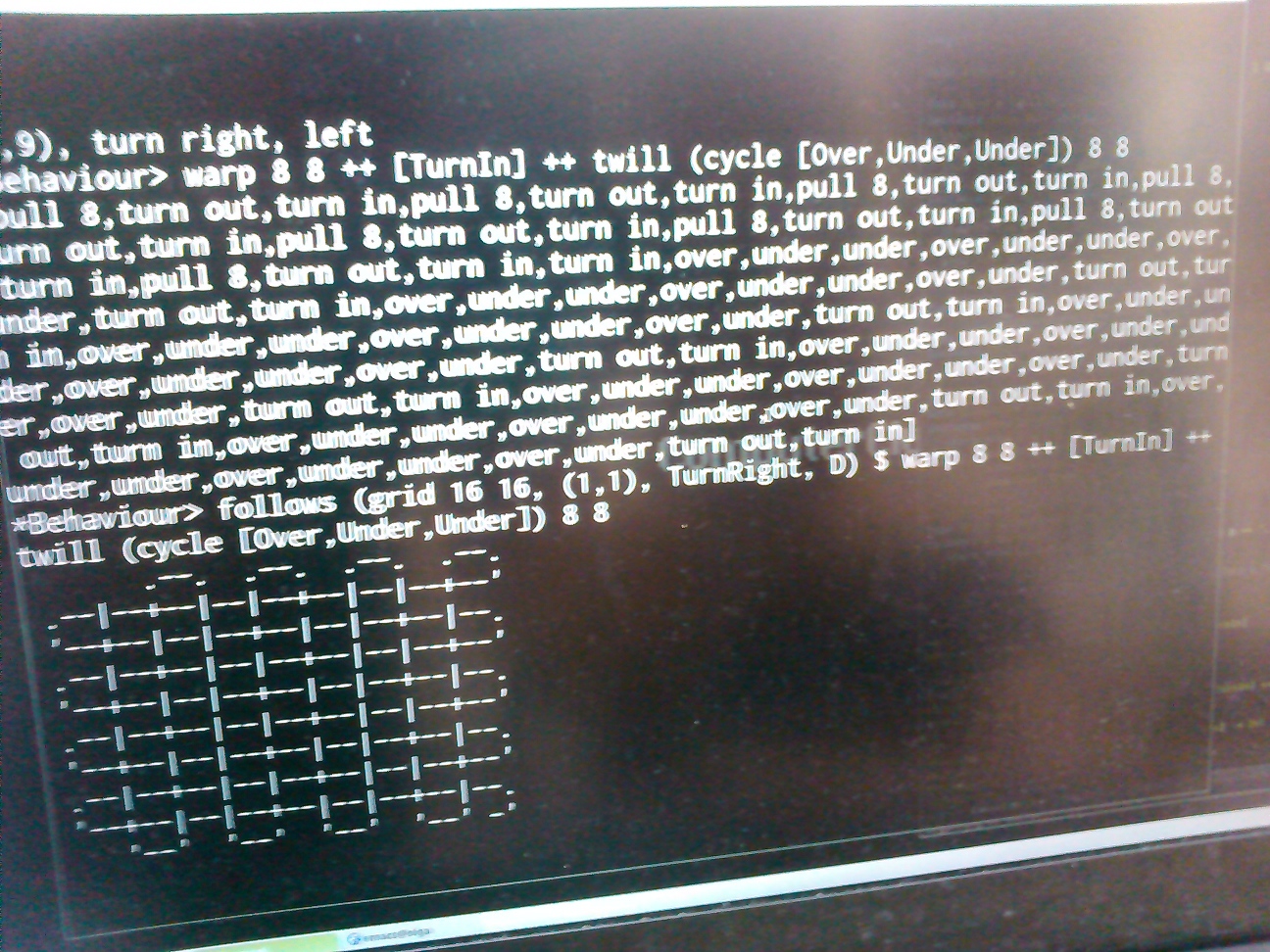

I’ve been prototyping models of a weave as a continuous thread, with some Haskell code. Here’s a quick demo which makes a plain weave, turns it into a 2-2 twill, then extends the weft to turn it into a warp, through which I then weave a plain weave:

Category: Uncategorized

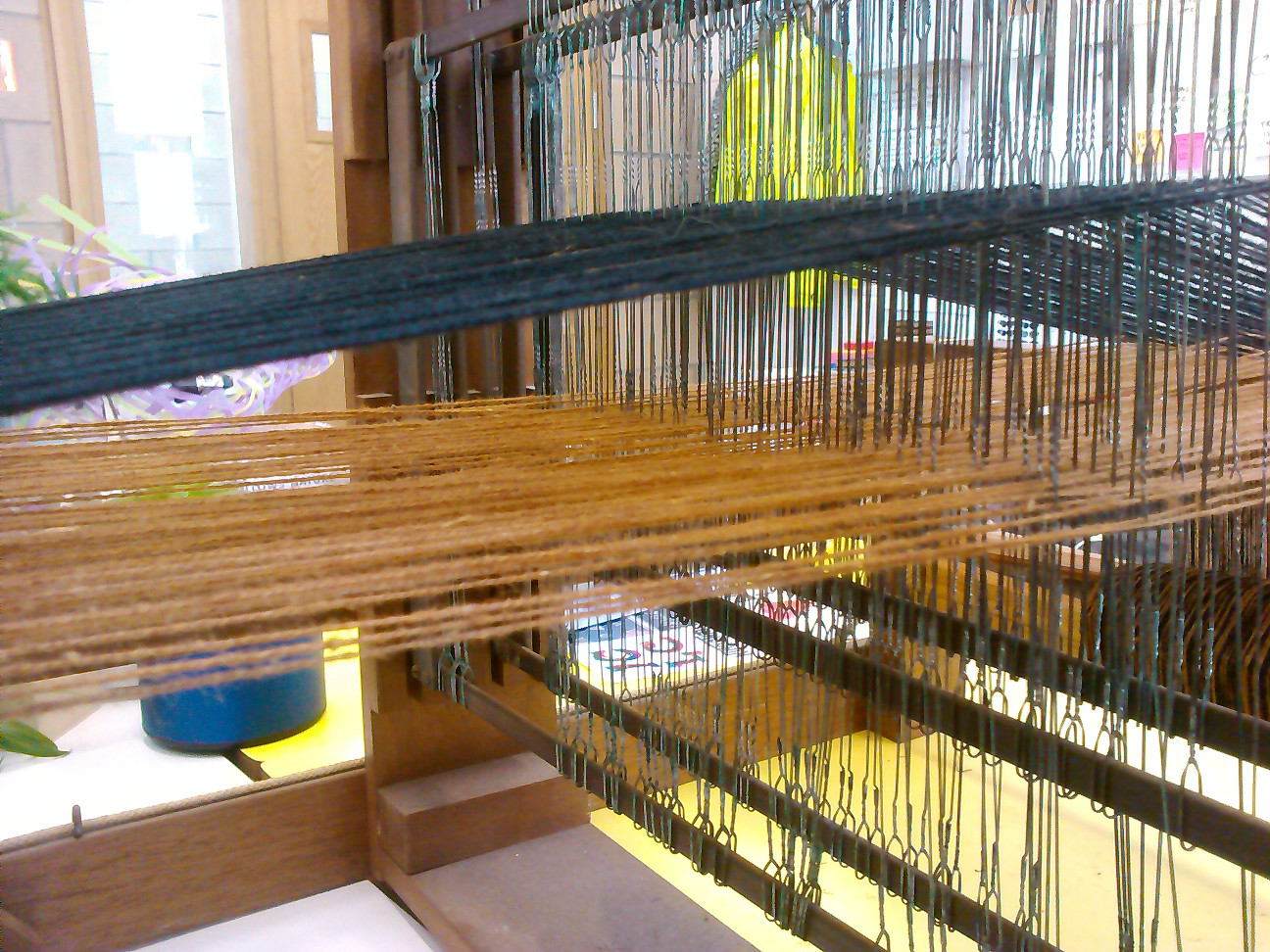

Warping a 4 shaft table loom

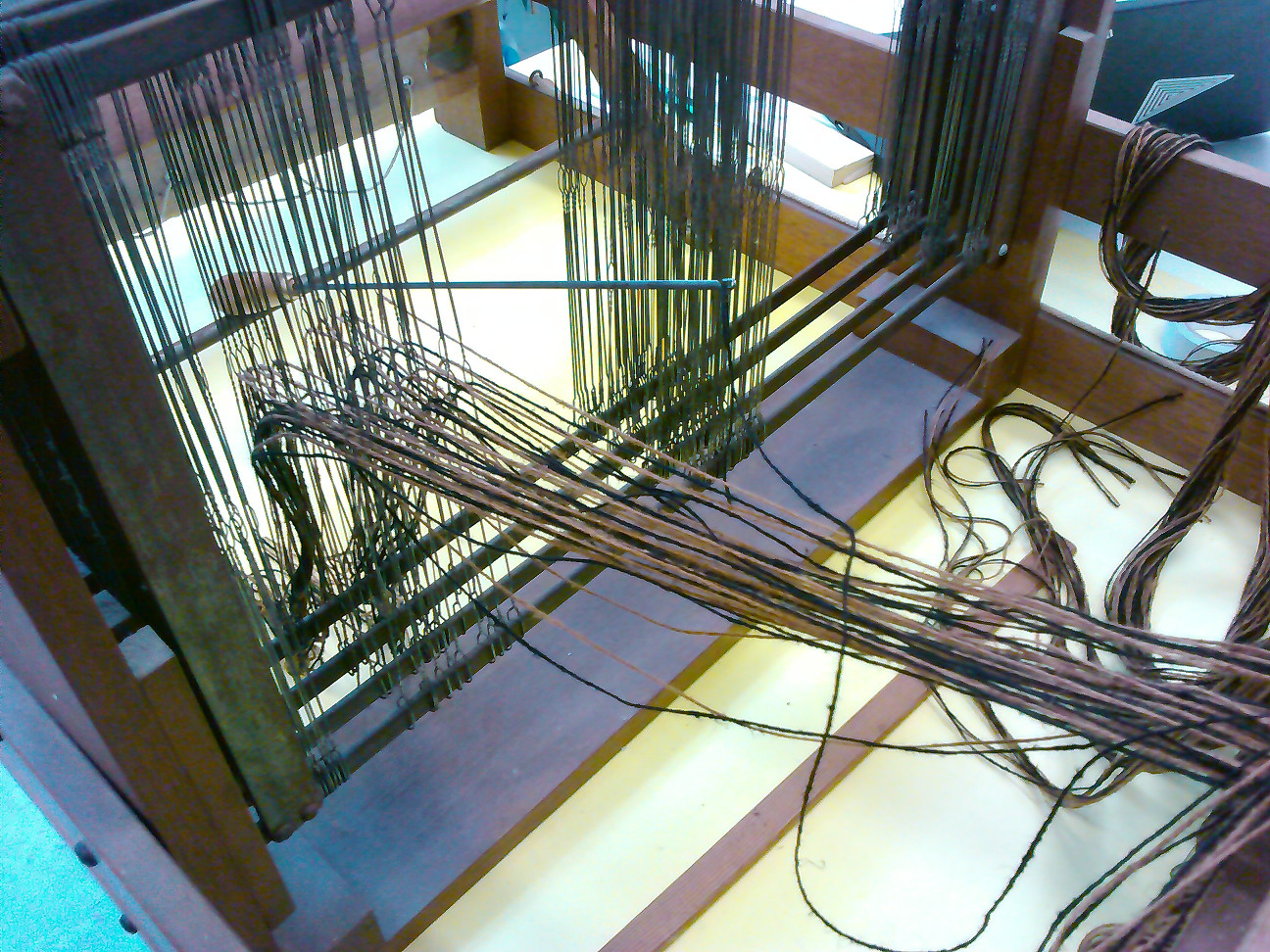

The next stop on my exploration of loom technology for the weavingcodes project (after building a frame loom and learning tablet weaving) has been learning how to use a 4 shaft table loom. This has been kind of daunting to me, as it’s a much more modern weaving device than I’ve been working with up to now (frame looms and tablet weaving can be considered to be both neolithic digital tech). I also couldn’t really figure out much from books on the warping techniques, as it’s difficult to get the idea through images – so I had to just kind of jump in and try it.

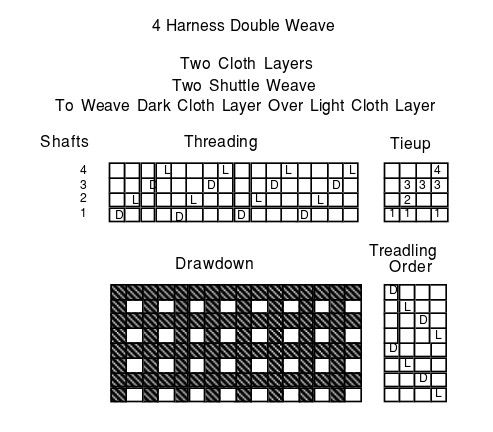

I decided to use the double weave draft plan to start with from my last post – partly as I want to try this technique, but also it’s pretty simple warp threading for a first attempt.

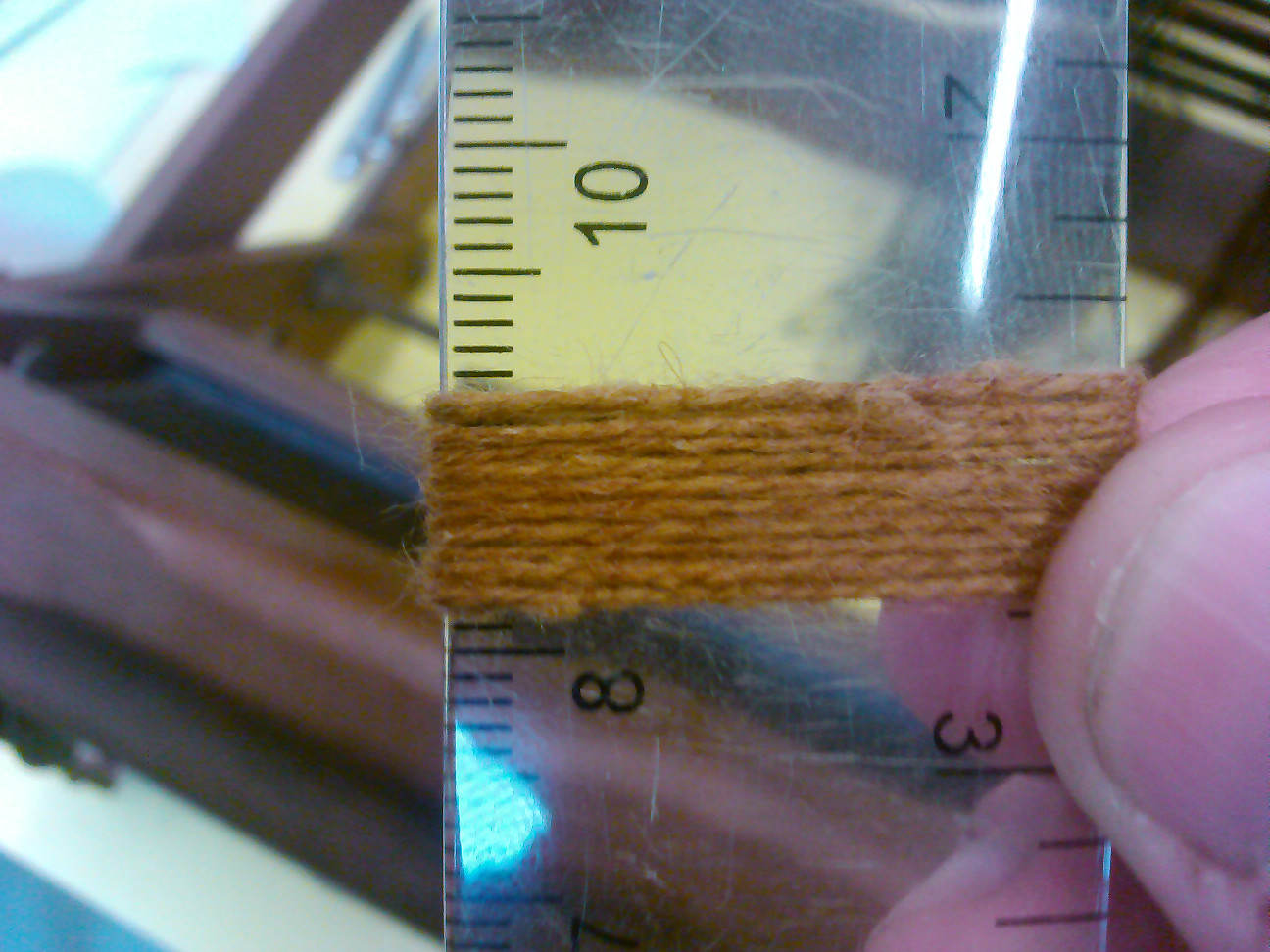

The next step was to choose the material. A while back I bought 200gms of good quality 8/2ne cotton/linen mix which I’ve been saving for something like this. In order to calculate the amount of fabric the yarn will produce you can wrap it lightly around a ruler:

This yarn is about 10 threads per centimetre, so we can use that to figure out roughly how many warp threads (or ‘ends’) to use – I decided on 160 ends in total (so ~16cm wide) comprised of the two alternating colours. I wound out two sets of 80 threads over a couple of metres, doing both colours at once to make it easier. I then attached each one to the back roller and wound them in a bit – this would have worked better later if I had used more bundles of fewer threads.

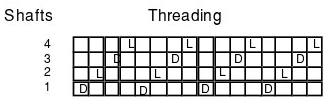

You can see in the picture I’ve also bolted a “raddle” (thing with nails) on the back beam of the loom to help space out the warp threads – this is important later on. Now we come to the heddles. The threading chart is what programs this part of the loom, which in turn forms a fixed instruction set of pattern possibilities for the weave. You can see the 4 levers that operate the frames in the photo above – these essentially give us 4 bits per weft of information. 2 of the 16 possibilities are invalid – as all frames raised or lowered doesn’t provide a working fabric. Using different sequences of these 14 combinations for each weft thread, the possibilities become mathematically huge – even with a fixed warp like this.

Reading the frames and warp colours from the chart to provide a sequence, you hook each warp end through the eye of the heddle – this was the most time consuming part of the process.

Once that is done, the reed – which is attached to the beater and used to pack down and keep the fabric evenly spaced, is threaded (or “sleyed”). The reed I used was a bit too course so I used two threads per gap – this could have done with being a bit more as it turned out.

With all this done the warp ends can be attached to the front roller and the whole warp can be wound on through the heddles and back again to check the tension. Of course in practice (and as it was my first time) it actually involved a lot of tangles and swearing, and two broken warp threads, fairly easily knotted back together. The raddle was essential in helping untangle the warp threads, but I also had to fiddle around with the tension a lot, retying the knots attaching them to the rollers and using plenty of sticks (it seems you can never have too many sticks when warping a loom). This is a test that the warp is threaded correctly, with all black threads (frames 2 and 4) lifted – phew!

After that we could try a little test weaving, going freestyle on the heddles.

It turns out the reed is a little too wide, meaning it’s stretching the warp out as the woven fabric finds it’s true width – switching to a new one is possible without needing to do the heddles again, so we’ll see how it goes. Compared with tablet weaving, this is far more mechanised and efficient in terms of fabric production, but the flipside to that is that you lose a lot of flexibility, and the loom is less responsive to particular material properties like this.

“The mystery of the drawdown”

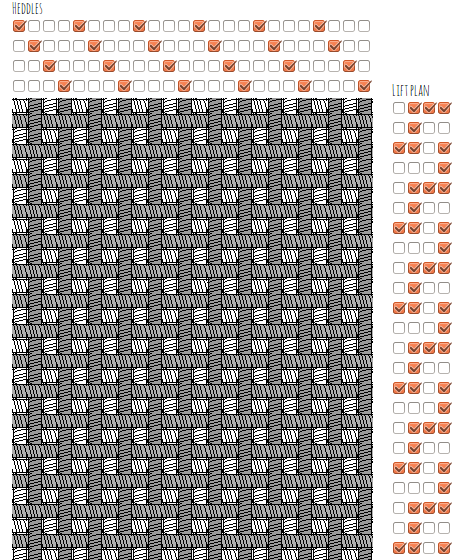

Double weave has intrigued me since first figuring out how it works with tablets – it shows how weaving is a 3D process, and is an example of shape making from code. It’s the starting point for more advanced methods for creating strong woven composite materials and structures. I’ve been reading this document by Paul O’Connor to understand the process for a 4 shaft loom. He includes this critique on current methods for visualising weaving:

The traditional method for creating the drawdown shows all the warp and all the weft threads in one layer. What is needed is a way to make two drawdowns, one for the top cloth layer and the other for the bottom cloth layer. Most of the commercially available computer weave programs display the drawdown in this same fashion, as a single layer.

This is a draft plan (the traditional notation technique) for double weave which contains the drawdown he’s talking about:

Drawdowns are designed for thinking about weaving as 2D pattern, and like any notation system they abstract a situation so we can reason about it, with the trade-off that they make it impossible to understand different aspects. This is a big problem we have in programming too – and is the reason we need to have many levels and hundreds of different languages to describe problems. I’ve noticed that if people (or organisations) stick with one too long, the specialisation starts to hinder ability to even recognise certain issues. It’s interesting to see such a clear analogy here.

In order to see what’s really happening with double weave, we need to switch to a different notation and look at the structure more closely:

Hopefully you can see that all of the black threads are sitting on top of all the white threads, and forms it’s own plain or tabby weave fabric. The same is true for the white threads underneath. Below is the same structure rendered in the weavecoding dyadic device – this shows the heddles that need raising to create the sheds in the lift plan, and you can see a repeating zigzag pattern. As an aside, I’ve noticed that there seems to be some kind of underlying categorisation of lift plan patterns which I’ve not found mentioned anywhere yet – something else to look into at some point.

Sonic Pattern 2

This week saw the return of “Sonic Pattern and the Textility of Code” as part of Sheffield Arts Week, a daytime symposium and nighttime performance, exploring ideas of textiles (weaving, knitting, stitching) alongside live coding, programming, mathematics and music, curated by Karen Gaskill (from Crafts Council) and Alex McLean.

I travelled to Electric Works, Sheffield, for the event with the Pattern Matrix in tow, ready to be inspired by talks from David Littler, Amy Twigger Holroyd, Sharon Mossbeck, Theo Burt, Gemma Latham and Matt Jones. Amongst these discussions was also a 20 minute talk from myself on behalf of FoAM kernow, introducing Weaving Codes/Coding Weaves.

David Littler presented us with ‘Yan Tan Tethera’, his documentary discussing the sound culture of textiles within English folk tradition, where rhyme, song and dance were used as counting systems during the process of creating textiles. Based around the traditional rhyme ‘Yan Tan Tethera’ (which, interestingly, counts in units of 5 – within weaving, knitting and cross stitching discussion, the beautifully divisible number 24 cropped up multiple times as a globally accepted ‘nice number’), the short film showed events celebrating work songs of times past and begs the question, do practitioners still do this? David’s Textile Folk Song project and video can be found on textilefolksong.co.uk.

Amy Twigger Holroyd, knitter and stitch-hacker from Keep & Share, introduced us to an area of her work that she does not discuss as often – mathematics. Previously I have been familiar with the social aspect of Amy’s research, and I loved hearing about this area of work. Similar to weaving, Amy described knitting machine punch cards as a binary device. A punch card is generally 60 rows long, and depending on the machine, can be around 24 stitches across (obviously there are variants on this). Amy uses math logic to design patterns, taking into account the technology she is using and the pattern she wishes to represent. With regards to computer programs that generate knitting patterns from image, Amy argues that they are perhaps not sufficient – computers do not have tacit knowledge, only mathematics knowledge. This is something that applies greatly to our own ideas of weaving simulation. Also really enjoyed hearing the algorithmic decisions that Amy applies to her stitch hacking.

Sharon Mossbeck explores cross-stitch as contemporary art. As an artist, Sharon explores religion, though which as an atheist she questions her own lack of beliefs. Cross-stitch is generally regarded as a ‘twee’ practice, bordering between art and craft. Sharon argues that cross-stitch is not regarded as ‘high art’ – maybe because there is a focus on skill over creativity. It seems that the majority of the stitchers focus on creating a piece using a pre-made kit, and focus on executing the piece neatly and expertly as opposed to stretching their creativity and approaching the medium from a different angle. Of course, there is ‘Subversive Cross Stitch’, a collective who create pieces inspired by quotes of popular culture and curse language, although they conform to traditional materials and grids. Sharon aims to bring cross-stitching into the contemporary, by subversing materials as well as message. She is currently working on a large-scale piece incorporating religious symbols, stitching into clay-soaked fabric.

During the following discussion with the artists, the topic of tensions arose. Both Amy and Sharon have experienced hostility towards their new approaches, wether that be accusations of devaluing the artform or their suggestions serving as a direct criticism to the practitioners. Amy argues that we can identify a tradition by the amount the change in the following years, a difference between now and then, so it’s important to move forwards. Considering tensions in our project and weaving, I can’t say I have encountered many personally, however this is an interesting question I will be bringing back to Falmouth.

Following a short break, Theo Burt presented some recent work. Theo is a generative art/computer/sound/video artist, who, for this particular project, wanted to take his subjectivity away from decisions regarding his pieces, as he felt his (or anyone’s) decisions would be too conventional. The project he presented took popular music and ran it through an algorithm to lose half of the track data and restructure it, keeping the main symbols and chords and ‘throwing away’ the formulaic build ups and drops. The result is beautiful music that you inherently recognise but as a trailing scent, enjoying instead the essence of the rearranged track. Theo also spoke about another process that splits a track into over 3000 slices of equal duration, and reorders them so that each slice will be followed by the most similar slice from those remaining. It was pretty eye-opening to see music approached in this way, especially popular music and club anthems that follow a certain code to become successful by satisfying the listener’s expectations.

After lunch, Gemma Latham spoke about weaving, coding and the theory of flow. It was great to finally meet Gemma as I have been following her work for a while, with common interests in weaving and Minecraft. As a participatory artist, she has been considering the theory of ‘flow’ in textiles, and how to achieve ‘flow’ – ‘flow’ meaning focus on the task in hand, navigating the fine line between anxiety and boredom whilst completing the task in an engaged, enjoyable and intuitive way. One workshop Gemma held in the Whitworth Art Gallery archives invited members of the public to punch weaving patterns on a single strip of paper, with a view to recreating a complete, large scale pattern. Alongside this, the participant’s experience was captured in a rating system. To visualise the data, Gemma presented the finished weave pattern encoded with the feedback results, and laser cut the final piece. Again, mathematics and digital ideas surrounded the practice of weaving via warp/weft over/under, and the idea of ‘flow’ is interesting to consider weaving through the practitioner’s engagement throughout the actual weaving process.

I spoke about the weaving codes/coding weaves project – it was great to have the experience of describing it in this context and people’s reactions to the pattern matrix were both enlightening and affirming. As well as introducing the project, I discussed my own adventures in tablet weaving and cryptography, followed by a demonstration of the pattern matrix. Although most did not initially understand the functionality upon approaching it (maybe I did not explain well enough?), everyone found it easy to engage with and seemed to enjoy figuring out how their draft pattern translated to the simulation, so served as a really good embodiment of the project.

The final speaker was Matt Jones. Matt finds pattern in everything, and also creates them, I’ve never seen anybody quite so passionate about pattern with the ability to see behind the arbitrary. If pattern is everywhere, Matt says, then code is too, and if the pattern is beautiful then it’s likely that the code behind it is also. This takes the idea of coding out of the utilitarian aspect into an artful, aesthetic yet still functional practicality.

After the talks, we moved on to Access Space for the evening performances, including sets from Theo Burt, Tim Shaw, Paul Wolinski, Xname and Alex McLean.

Sonic Pattern debrief

The second Sonic Pattern and the Textility of Code series of symposia is a collaboration between Karen Gaskill (who is currently lead curator of Crafts Council innovation) and myself in a variety of guises. The second one took place earlier this week, and went really well, with a range of provocative talks and performances around craft, technology and touching the abstract.

Videos of some of the presentations and performances will be shared soon, but here are some quick reflections.

Particularly interesting were recurring themes across the quite different practices. One was exploration of the low brow, of working with peoples reactions against certain practices (even sneering), to confound expectations and break open misconceptions. This was most clearly seen both in Sharon Mossbeck‘s conceptual approach to cross-stitch, finding rejection both by groups of artists and craftspeople, and Theo Burt‘s phenomenal process-based reworkings of what could be called over-produced mainstream dance music. When the presenters were talking about making people aware of the rules in craft, different approaches to them, and how to encourage people to break them, it became difficult to keep in mind that we were talking about e.g. knitting and not politics.

Another theme I spotted was anxiety, for example artists expressing anxiety about mathematics despite textile work being full of numbers (the number 24 in particular cropping up as being a “good” one in textiles for it’s excellent divisibility). Also also the anxieties of self-identifying as a digital or analogue artist (although I’d argue all artists have always been both), and the differing statuses that people hold these terms at.

Another theme was the ‘long view’ shared by some presenters, that pattern (as a digital artform) is ancient, embedded in our culture, and as Matt Jones got across by sharing his perception of the world with us, basically everywhere. This long view is core to Weaving Codes, as our own Francesca Sargent spoke about in the symposium.

I could say much more but will save my words until the videos are up!

Quipu coding with knots seminar at the Institute for Music and Media Düsseldorf

Renate Wieser and Julian Rohrhuber are the people who first introduced Ellen with Alex and me, and Julian is also officially a member of this project’s Steering Committee – so it’s great to be able to invite him to co-author this post on our ‘coding with knots’ seminar at the Institute for Music and Media in Düsseldorf. My teaching role there gives us an opportunity to look at one of the intriguing technology histories related to the weavingcodes project, the Inca quipu.

We decided to base the seminar around finding ways to understand the quipu and the data they contain in their knots. Much of this is still a mystery to archaeological research, and while we can’t be expected to make great breakthroughs in ‘cracking the code’ over a couple of days – there is value in bringing a cross-disciplinary approach to the problem as artists, musicians and programmers.

This was also to be our first experiment in remote teaching, with Dave working from Foam Kernow in Cornwall and using online tools to create a shared space with IMM in Düsseldorf. We could write quite a bit more about this aspect alone, for example it turned out that mirrors are critically important in this situation:

We had prepared a small ‘toolchain’ for the seminar, starting with the Harvard quipu database which currently provides data for 248 quipus. We also had python code for processing/analysis of this data, using graphviz for visualisation and a supercollider parser for the dot files used by graphviz so we could move on to sonifying them.

To start with Dave briefly introduced the Inca civilisation, some of their scientific achievements and very different understanding of time and how much of this culture remains in current societies in the region. We looked at the context in which we think quipus were used, as the basis of organisation (with threads) of a large empire with no money or other forms of written record. Moving on to our tools we explored graphviz, and experimented a little with improving the visualisation then moving in to the world of supercollider we explored the data provided by the dot files.

It turned out to be too limiting to interpret only the graph drawing instructions in supercollider, so we found we could include more complete information as ‘hidden data’ (twist, length of the pendants or type, value and spin of the knots). These extra data elements could be added in such a way as to make them silently ignored by graphviz for visualisation. This saved a lot of time needing to come up with another intermediate format.

We also needed some overview of the entire database, in order to search for interesting quipu to sonify. Various quipus have been partially understood, for example some possibly contain data structures for calendar information based on solar and lunar time. Others contain accounting data, with matching hierarchical records found in other quipus. The most mysterious are so called ‘narrative quipus’ which don’t seem to fit the decimal system at all, meaning the knots don’t line up neatly in rows for reading in term of units, tens, hundreds and thousands.

When the significance of the structure of a specific medium is unknown, sonification can be a way to gain new insight. There are various reasons for this, which have partly to do with the way understanding is coupled with perception, partly also simply with the fact that listening takes time and this is time we spend with absorbing a texture and its potential internal connections.

But there are very many different sonification approaches in a sonification laboratory – which one to choose? In the seminar we discussed for a while the general problem, namely how to understand graphs as time series, which is not always easy: many different non-trivial paths are possible. The quipus have a very distinct shape: a rather long series of small graphs, each of which have a couple of potentially relevant, but very different dimensions (such as color, number, length). Because sonification is particularly good at giving insight into parallel serial data, our first sketch was to treat the series of pendants from one end of the primary cord to the other, as a series in time (as you would do with a text).

The current state of research makes it plausible that the colours used in quipus are of significance, but it is so far unclear of what. The shades of colours are subtle, as is their possible meaning. To start with, we sonified the colour pattern of the quipu UR004 in a very simple way: a series of very short sine tone chords represent the red, green and blue components:

This causes tones of grey to sound like a single tone, and the difference between components stands out as distance between separate partials. A rather simplistic sketch as it is, it nevertheless revealed a surprisingly rich rhythmic structure, which would be easy to overlook visually. This gave us some confidence that we should pursue this direction a little further.

The next day we began by going back to the data formats, and Dave included a number of data dimensions to the graphviz files. Especially interesting were arrays of colours, which represent alternating coloured threads, and some binary opposed properties, like ply and knot orientation. Some more reading about the interpretations of archaeological findings, we found two promising quipus which made us curious. The paper by Juliana Martins on the astronomical analysis of an Inca Quipu pointed to two interesting candidates from Leymebamba (UR006 and UR009), which we began to work on in the afternoon.

Here is a first result (UR006):

You can hear in this example that each short sound event (about 1/10 of a second an shorter as we go down the subsidiaries) has a number of independent timbral properties. Here is an overview of what “quipu dimension” is mapped onto which sound dimension:

| colour | sine tone spectrum of three partials |

| branching level | duration between sound grains (inter onset duration) |

| colour | sine tone spectrum composed of three partials |

| pendant length | duration of each sound grain (relative to inter onset time) |

| pendant attach (verso or recto) | pan position left or right channel |

| pendant ply (S or Z) | envelope shape (audible as “inversion effect”) |

| unknown values | are usually interpreted as neutral (pan) or low (colour) |

The moments of audible acceleration result from areas with many pendants that have subsidiaries (side branches). In various dimensions rhythmic patterns appear, which partly coincide and partly remain independent. Also, in some moments, we can hear sudden changes of the overall pattern, indicating a transition into a different logic.

Sonic Pattern and the Textility of Code

We’re happy to be involved with the second Sonic Pattern and the Textility of Code event, to be held in Sheffield on 17th June 2015. It’s a collaboration with our Weaving Codes AHRC digital transformations project, the Crafts Council, and the EPSRC Communities and Culture Network+, co-curated by Karen Gaskill and myself (Alex McLean). The daytime discussion will include a presentation by Francesca Sargent on our project, including the Pattern Matrix.

It’ll be a full day of activity, with a symposium during the day featuring six diverse speakers, and an evening of audiovisual performances. All will explore how code, sound, image and threads allow us to both sense the abstract and conceptualise the tactile.

For more info, including booking details, see the Sonic Pattern website.

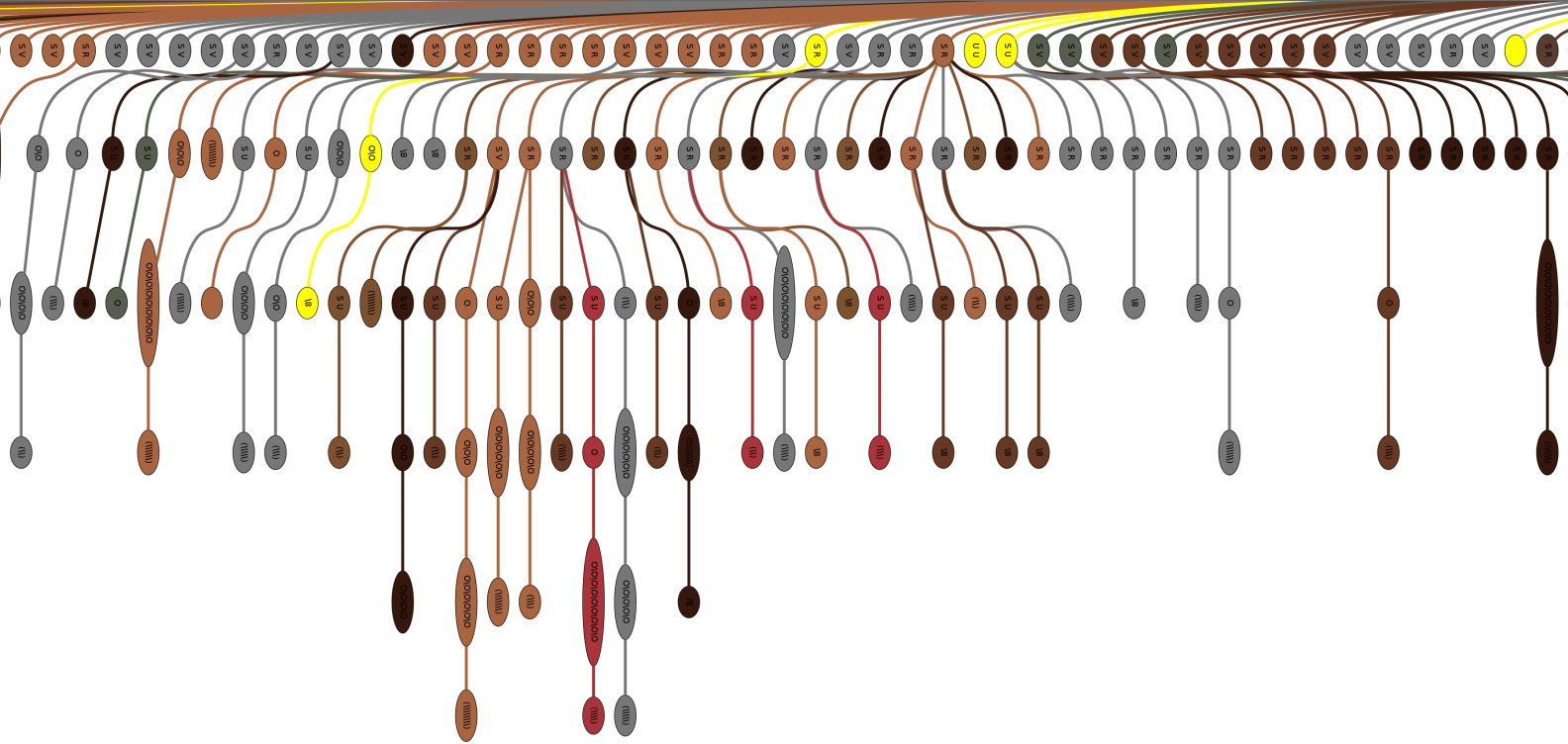

Coding with knots: Inca Quipu

This week I’m teaching at IMM Düsseldorf with Julian Rohrhuber which has given me a chance to follow up a bit on Inca Quipu coding with knots, a dangling thread from the weavecoding project. Quipu are how the Incas organised their society, as they had no written texts or money – things like exchanges (for example from their extensive store houses) were recorded via knots. Researchers have been able to decode the basic numeric system they used, but 20% of the quipu seem to follow a different set of rules, along with extra information encoded via thread material, twist direction, colour and other knot differences. I’ve written a python program for converting the Khipu Database Project excel charts into graphviz files for visualising:

The knots are described in ascii art, with S and Z relating to the ply and knot ‘handedness’ direction they are tied in:

O : a single knot O/O : two single knots tied in S direction (it's rotated 90 degrees :) (\\\\) : a long knot of value '4' tied in the Z direction /8 : end (figure of 8) knot tied S direction

The pendant nodes also have labels describing their ply direction and the side the attach on, so “S R” is S ply & recto attached.

The hardest part of this has been a bit of more recent media archeology to figure out the colour values, I’ve had to cross reference the original Ascher-Ascher Quipu Databooks published in 1978 which contain their own colour system which more or less maps to the NBS-ISCC Munsell colour chart originally proposed in 1898. Luckily that site provides hex colour values – hopefully they are vaguely accurate, the current lookup table is here:

colour_lookup = {

"W": "#777777",

"SR": "#BF2233",

"MB" : "#673923",

"GG" : "#575E4E",

"KB" : "#35170C",

"AB" : "#A86540",

"HB" : "#5A3D30",

"RL" : "#AA6651",

"BG" : "#4A545C",

"PG" : "#8D917A",

"B" : "#7D512D",

"0B" : "#64400F",

"RM" : "#AB343A",

"PR" : "#490005",

"FR" : "#7F180D",

"DB" : "#4D220E",

"YB" : "#BB8B54",

"MG" : "#817066",

"GA" : "#503D33"

}

Weavecoding Munich

Ellen’s exhibition in Munich was always going to be a pivotal event in the weavecoding project – one of the first opportunities to expose our work to a large audience. The Museum of casts of classical sculptures was the perfect context for the mythical aspects of weaving, overlooked by Penelope and friends with her subversive woven/unwoven work, we could explore the connections between livecoding and weaving.

Practically we focused on developing the tangible weavecoding exhibit for events later in the week, as well as discussing the many languages we have developed so far for different looms and weaving techniques. One of our discoveries is that none of the models or languages we have created seem sufficient in themselves – weaving could be far too big to be able to be described or solved from a single perspective. We’ve tried approaches describing weave structures from the actions of the weaver, setup of the loom and structure of the fabric – perhaps the most promising is to explor the story of weaving from the perspective of the thread itself.

One of the distinctive things about weaving in antiquity is how multiple technologies were combined to form a single piece of fabric, weaving in different directions, weft becoming warp, use of tablets vs warp weighted weaving. To explain this via the path of a single conceptual thread crossing through itself may make this possible to describe in a more flexible, declarative and abstracted manner than having to explain each method separately as if in it’s own world.

The pattern matrix has now been made into good shape for explaining the relationship between colour and structure in pattern formation. For the first time we also used all 4 sensors per block on the bottom row which meant we could use a special “colour” block that the system recognises from the normal warp/weft ones and use it’s rotation to choose between 8 preset colour settings. This was quite a breakthrough as it had all been theoretical before.

Adding this more complex use of the magnetic patterns meant that Alex could set up the matrix as a tangible interface for his tidal livecoding software meaning Ellen could join us for a collaborative slub weavecoding performance on the Saturday evening. The prospect of performing together was something we have talked about since the very beginning of the project, so it was great to finally reach this point. The reverb in the museum was vast, meaning that we had to play the space a lot, and provide ‘music for looking at sculptures by’:

Textile MATRIX exhibition opened

Since Tuesday the 28th of April, visitors can see the works of Ellen Harlizius-Klück in the Museum for Plaster Casts of Classical Sculptures in Munich. On display are recent works on ancient textile resonstructions, but also artwork from recent years like Quilts and textile installations.

29. April to 7. June 2015, Textile MATRIX, Works of Ellen Harlizius-Klück, Museum for Plaster Casts of Classical Sculptures Munich, Katharina-von-Bora-Straße 10, 80333 Munich, GERMANY.