The second week of intense work on weavingcodes/codingweaves took place in the north of England, and began with a talk at the New Mechanics Institute show and tell meeting in Leeds. This was a good place to pick up from the previous week in Denmark as it included a talk on pixel art from the early days to contemporary forms that had many similarities with our slides.

The first half of the week was spent in Leeds University at the Interdisciplinary Centre for Scientific Research in Music where we met Tim Ingold whose books (e.g. Making: Anthropology, Archaeology, Art and Architecture) have been a big influence on the project. One of the things we discussed with Tim was the cyberspace myth – the idea that computing is intangible and exists in some “other world” (or in a “cloud” somewhere) which is increasingly problematic. The need to highlight the physical basis of computation is one that this project is well placed to address – and if we consider weaving to be a form of computation, then it may be able to inspire approaches to programming that have at least three thousand years of history behind them. Tim also discussed knowledge as movement, his understanding of tacit knowledge – that which is otherwise unwritten or unspoken. Tacit knowledge is fluid and exists underneath a counterpart, called ‘articulated knowledge’ which is fixed by definitions. Culturally we have a bias towards articulated knowledge, and the idea of an unspoken knowledge is something which I realise I am trying to deal with in my teaching activities, but I’ve never been able to suitably describe it.

On day 2 we met with Leslie Downes – a retired professional weaver, whose woven structures have gone into space, been used in jet engines and bullet proof vests.

There are many places where woven structures are superior to other kinds of manufacturing, but at the same time there is a lack of knowledge about weaving technology in engineering in general. Industrial fabric weaving has focused on increasing speed and production output while the kind of looms needed for materials like carbon fibre need to focus on precision. Leslie talked of occasions where he had to return to using hand looms to try out prototypes and how simulations of fibre interactions in weaving exist, but are unnecessary and deficient compared with prototyping with the actual materials. In weaving, as in computing, older tends to mean less restricted, as well as slower. New developments add to, rather than eclipse older ones.

The main feeling I had from Leslie was that his approach to technology came from a combination of an ability to reason about material based on a deep understanding of the capabilities of the looms themselves, how they can be adapted for each job (e.g. a project where he had to cut down the middle of a huge loom to remove a metre or so) mixed with experience in working with people to understand their needs. This generalist approach to knowledge is so lacking in society that it becomes highly regarded.

For the second part of the week we moved to Sheffield, and had breakfast with Luigina Ciolfi researcher in Human-Centred Computing. Lui’s input was both valuable and timely, as she pointed out that one of the key elements of interest is that nature of our collaboration, rather than any products we may or may not come up with. As such we need to be careful that we take the time to document our process and decision making.

After breakfast we headed into the woods – to a temporary base in The J G Graves Woodland Discovery Centre to shift into plotting and planning mode.

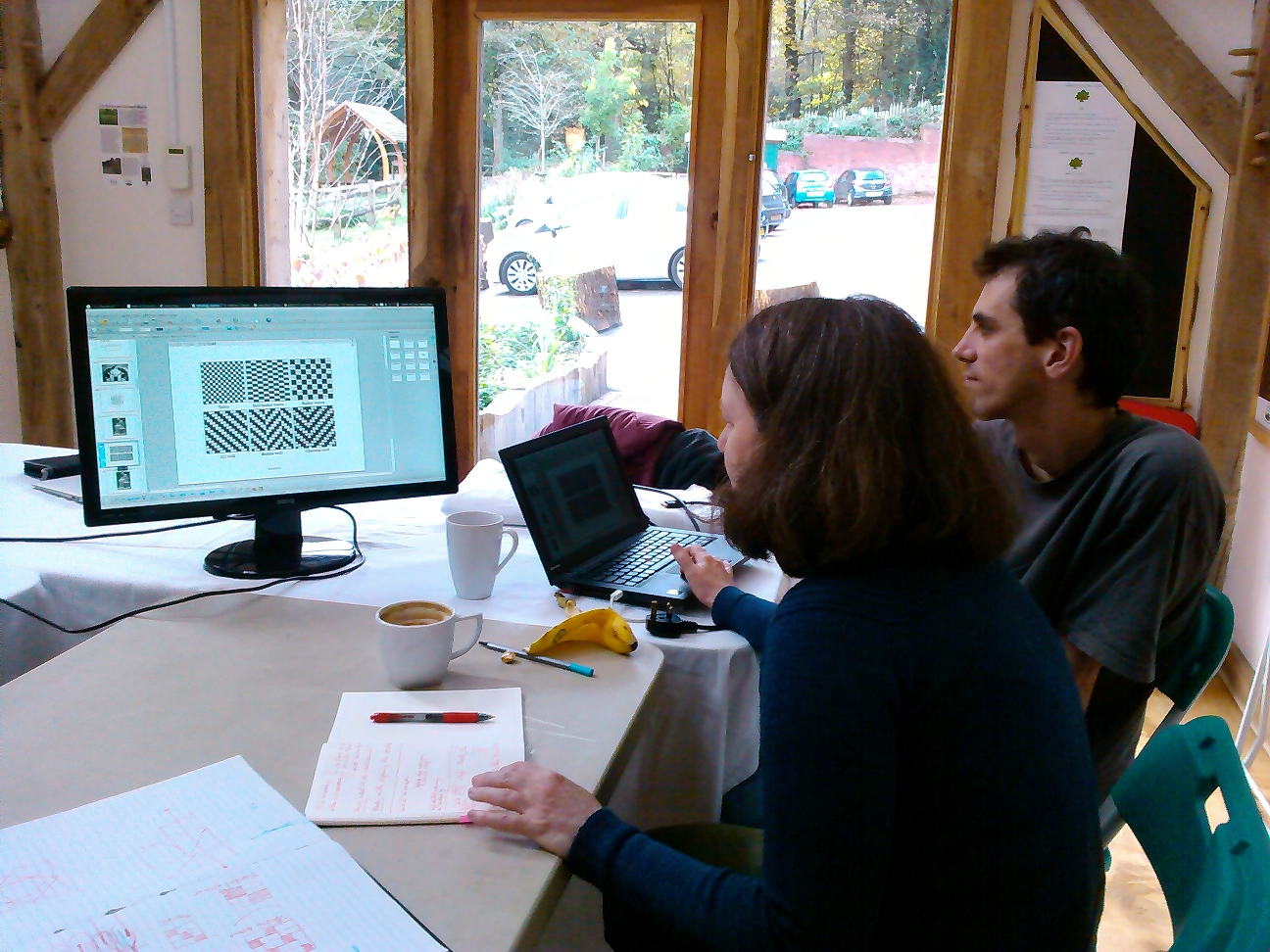

Emma Cocker joined us again, and helped to restrengthen the kairotic and poetic roots of our thinking and we were visited by the lovebytes crew to discuss the use of weaving and livecoding for teaching children. I set up the flotsam tangible programming prototype for its first ever use by anyone other than me. This involved a bit of code review/pair programming with Ellen in order to fix bugs in the weave generating algorithm.

We face challenges with our collaboration in both directions between our practices. On the one hand we have normal software decisions, is what we make going to be online or offline? Do we prioritise flexibility or accessibility for our choices in platforms and languages? How does what we do connect best with Ellen’s existing programming experience?

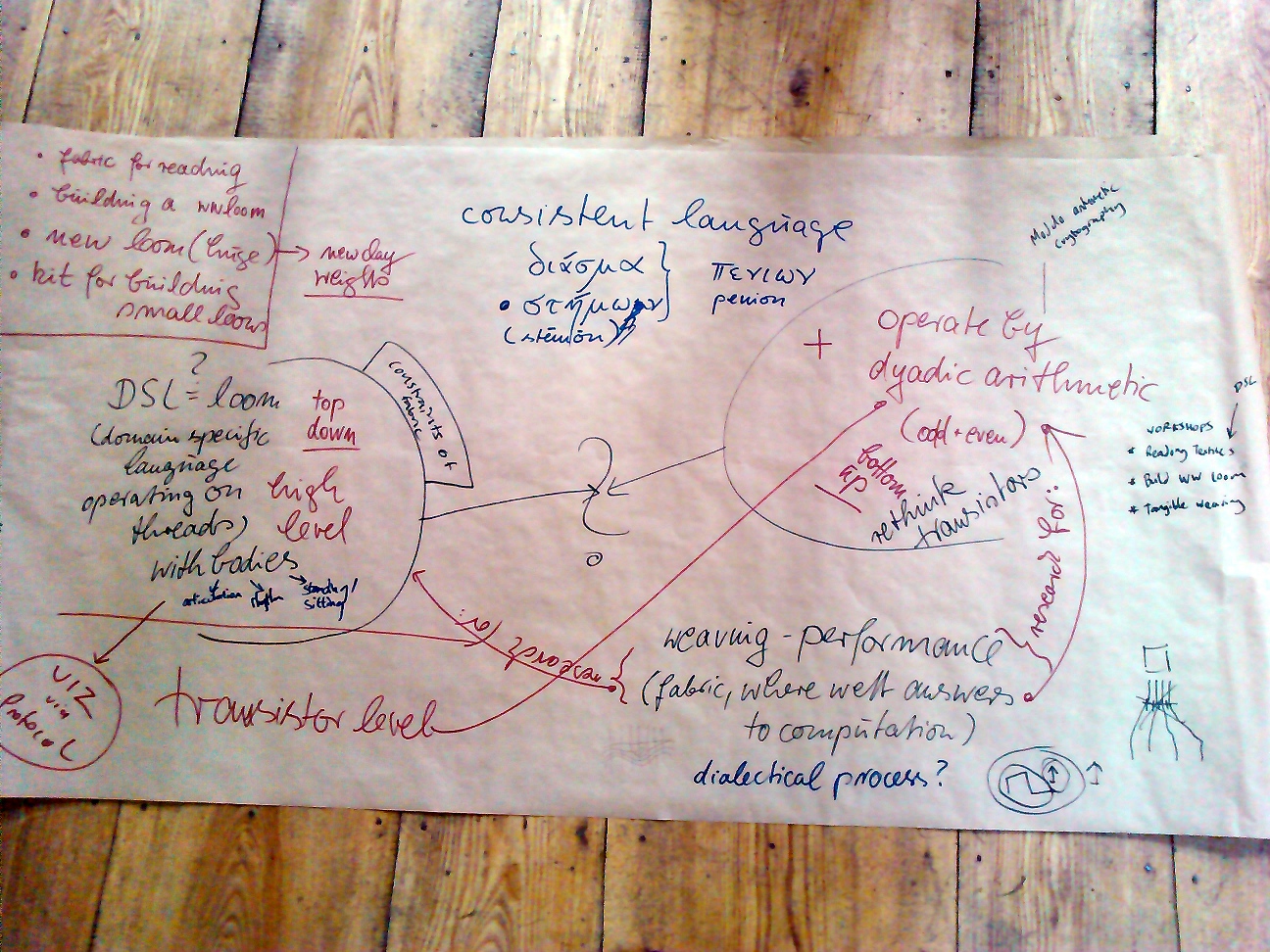

What we have decided is to work on a series of prototypes rather than focus on a monolithic development. The task then is to make sure we use common language for concepts across the project (perhaps using the concepts in the ancient Greek as a grounding influence). Similarly, using protocols and formats to share common things between experiments – and fitting with existing programs and archives already in use where practical.

In the other direction, much of our discussion revolves around clarification of weaving practicalities and explanations – both of weaving in general and concepts and styles in use in antiquity. Both Alex and I need to start weaving if we are going to have a subtle enough understanding of the material we are dealing with. To this effect Alex already has a commission for a warp weighted loom in the works and I need to warp up the Harris loom.

We also have some fairly concrete projects to think about over the coming months, for example providing a good live-codable explanation of weaving to replace Ellen’s previous windows program as well as looking into the possibilities of using tangible programming in an art installation.

One thought on “Learning about thinking and weaving in Leeds and Sheffield”